IRS Penalty Abatement: How to Get IRS Penalties Waived

IRS penalties can be onerous, adding thousands of dollars to a taxpayer’s balance with the IRS.

That is, of course, the bad news.

The good news is that it is actually possible to get IRS penalties abated using one of two methods:

- First-time penalty abatement

- Reasonable cause abatement

First-time penalty abatement is mechanical, limited in use, and applicable to only three penalty types; reasonable cause abatement can apply to any IRS penalty but requires more work and in most cases documentation.

Here’s what you need to know about both of these ways of getting IRS penalties erased.

Note that this article is about civil penalties the IRS assesses; criminal penalties are another matter entirely.

Table of Contents

The IRS Gets It Wrong Sometimes

Now, the first thing you need to understand about penalty abatement requests — at least the ones that are not automatic — is that the IRS gets it wrong sometimes.

The individual on the other side of the letters we send to the IRS requesting penalty abatement for our clients sometimes get it wrong.

Sometimes, even though a client’s situation clearly qualifies for penalty relief according to the IRS’s own Penalty Handbook, which can be found in Internal Revenue Manual Section 20.1, the person at the IRS reviewing our request will deny it.

When this happens, we don’t sweat it — we have to go to Appeals. And I will talk more about that later in this article.

But for now, I just want you to know that by the time you finish this article, you just might know more than many folks at the IRS.

And don’t take this from me. Take it from the IRS’s own Penalty Handbook, which anticipates that its employees will make mistakes when it comes to penalty abatements when it says:

“Strive to make a correct decision in the first instance. A wrong decision, even though eventually corrected, has a negative impact on voluntary compliance. Provide adequate opportunity for incorrect decisions to be corrected.”

So before we get into the nitty-gritty here, just know that.

The Purpose of IRS Penalties

Another thing to keep in mind when we talk about penalty relief is the purpose of IRS penalties.

The stated purpose of IRS penalties according to Internal Revenue Manual Section 20.1.1.2(1) is not to make more money for the government — although that is obviously a side benefit to Uncle Sam — but rather “to encourage voluntary compliance,” which for most taxpayer consists of simply preparing an accurate tax return, filing it on time, and paying any related tax due.

Federal income tax compliance in the United States is “voluntary” in the sense that taxpayers self assess their tax liabilities — typically through filing an income tax return — and making voluntary payments on this obligation.

The IRS’s obligation in this arrangement is to provide taxpayers with the information they need to comply with their tax obligations as well as forms for taxpayers to use to compute their own tax liabilities.

And the IRS believes that imposing penalties on non-compliant taxpayers encourages voluntary compliance by:

- Defining what compliant behavior looks like

- Defining the consequences for not being compliant

- Providing monetary sanctions against taxpayers who are not compliant — sanctions that are severe enough to deter noncompliance and are proportionate to the offense

This is important when we talk about penalty relief for reasonable cause later in this article, which is a fairly subjective thing.

And I’ll talk about this more later in this article, but one thing you want to communicate to the IRS when requesting penalty relief for reasonable cause is that there was a very good reason why you were not compliant with your tax obligations in the past, but now you are “back to normal” and going forward you will be a good little taxpayer and file your tax returns on time and pay your taxes timely as well.

Also keep in mind that the IRS instructs its employees to view each penalty abatement case in an “impartial and honest way,” meaning that the case should be approached not from the government’s or the taxpayer’s perspective but in the interest of enforcing the tax laws fairly and impartially.

Penalties: Multiplying Like Rabits

In 1955, the tax code only had 14 or so penalty provisions; today, it has over 150!

First-Time Penalty Abatement

But before we get into the reasonable cause penalty abatement, which is a bit more subjective, let’s talk about the more straightforward kind of IRS penalty abatement you can get, and that is the first-time penalty abatement.

In 2001, the IRS introduced the first-time penalty abatement. And despite its usefulness and having been around for over two decades, many taxpayers still don’t know about it.

Now, contrary to what its name implies, taxpayers can actually use first-time penalty abatement multiple times — and I’ll talk about how later.

But first, let’s discuss the basics.

What Is First-Time Penalty Abatement?

First-time penalty abatement is the complete abatement of a taxpayer’s failure-to-file, failure-to-pay, or failure-to-deposit penalty due to the taxpayer’s previous compliance.

So there are over 100 IRS penalties out there, but the first-time penalty abatement can only be used on these three:

- Failure-to-File Penalty: This is the penalty that the IRS assesses if you file your tax return late. This penalty is equal to 5% of the amount of tax you owe on the return per month or part of the month that your tax return goes unfiled past the due date or the extended due date if you extended your return. It maxes out at 25% of the amount of tax you owe.

- Failure-to-Pay Penalty: This is the penalty that the IRS assesses if you pay your taxes late after April 15 when taxes are due for the previous year. This penalty is equal to 0.5% of the amount of tax you owe on the return per month or part of the month that you have not paid your taxes. It also maxes out at 25% of the amount of tax you owe. If you owe both the failure-to-file penalty and the failure-to-pay penalty, the failure-to-pay penalty is subtracted from the failure-to-file penalty each month so that you never accumulate more than 5% of your balance in penalties every month. And combined, these penalties max out at 47.5% of the tax you owe after a little over four years.

- Failure-to-Deposit Penalty: This is the penalty that the IRS assesses on employers who don’t make their employment tax deposits on time, in the right amount, and in the right way. So if you’re an employee, you know that you get a lot of money taken out of your paycheck every pay period for taxes — as far as the IRS is concerned, you’re looking at federal income taxes, Social Security taxes, Medicare taxes, and the Federal Unemployment Tax. Your employer is responsible for depositing these payments to the United States Treasury. If they do not do so or if they do so late, the IRS charges a penalty between 2% and 15% of the unpaid deposit.

The first-time abatement is not penalty specific, meaning that there is not a first-time abatement for the failure-to-file penalty and a separate first-time abatement for the failure-to-pay penalty; if you are granted first-time penalty abatement for a given tax year, all of the three penalties indicated above are wiped away for that tax year.

Although the Internal Revenue Manual generally speaks with respect to individuals getting their failure-to-file penalty and failure-to-pay penalty abated using first-time penalty abatement, I have had no problem obtaining an abatement for partnership and S corporation failure-to-file penalties as well.

Note, however, that the Internal Revenue Manual explicitly states that first-time penalty abatement cannot be obtained for penalties associated with estate tax returns, gift tax returns, or returns that are attached to another return (such as a Form 5471 or Form 5472); the only way to abate these kinds of penalties is for reasonable cause.

How to Qualify For First-Time Penalty Abatement

In order to qualify for first-time penalty abatement, you must meet these criteria:

- In Filing Compliance Under IRS Policy Statement 5-133: You must have filed all required tax returns currently due, which under IRS Policy Statement 5-133 generally means that you must have filed at least the last six years of returns insofar as you had a filing requirement. And it’s OK if it’s currently between April 15 and October 15 and you extended your tax return for last year. Note that IRS-created substitutes for return do not count toward this requirement.

- In Filing Compliance For the Three Years Before the Tax Year in Question: You must have filed all required tax returns for the three years prior to the tax year you are seeking first-time penalty abatement for.

- In Payment Compliance: You must have paid or arranged to pay all taxes currently due. Note that if you are in a short-term payment plan or an installment agreement with the IRS, and you are current on your required payments, you meet this requirement.

- Clean Penalty History: You do not have any unreversed IRS penalties — other than estimated tax penalties — for the three years prior to the tax year you are seeking first-time penalty abatement for. Also, you cannot have any penalties that were reversed for first-time abatement or tolerance.

Based on the second and fourth criteria above, a taxpayer may only qualify for first-time penalty abatement for every three tax years.

How to Get First-Time Penalty Abatement

When it comes to requesting first-time penalty abatement with the IRS, you have two options:

- Making the request over the phone by calling the toll-free number on your penalty notice

- Making the request via a letter sent to the address on your penalty notice

Personally, I prefer making the request over the phone because 1) it’s easier and 2) you can make multiple attempts if the first IRS representative you speak to denies your request.

Why would an IRS representative deny your request? This is because the IRS representative is using a computer program called the Reasonable Cause Assistant (RCA) to determine if a taxpayer qualifies for penalty abatement — and in my experience some IRS representatives don’t know how to use it correctly!

Note that if your penalty is significant, the IRS representative may inform you that you will need to write the IRS a letter to request first-time penalty abatement.

If this is the case — or if you simply prefer to write a letter rather than calling — you would write a letter to the IRS explaining why you qualify for first-time penalty abatement for a particular tax year and mail this letter to the address on your penalty notice.

If You Are Approved For First-Time Penalty Abatement

If the IRS approves your request for first-time penalty abatement over the phone, they will let you know on the call.

And in all cases where the IRS grants first-time penalty abatement, it will send you Letter 3503C that says something to the effect of:

We are pleased to inform you that your request to remove the failure to file and failure to pay penalties has been granted. However, this action has been taken based solely on the fact that you have a good history of timely filing and timely paying.

This letter also clarifies that if you still have a balance for the tax year in question, the failure-to-pay penalty will continue to run until the tax is paid in full but that after the tax is paid in full, the taxpayer can request abatement of that additional failure-to-pay penalty.

And the Internal Revenue Manual clarifies that this abatement of the additional failure-to-pay penalty that continue to run after this initial first-time abatement was granted can be abated under first-time abatement as well.

If You Are Not Approved For First-Time Penalty Abatement

If you are not approved for first-time penalty abatement, the IRS will send you a rejection letter informing you of the rejection.

In this rejection letter there will be information about how to appeal the IRS’ decision with the IRS Office of Appeals.

If you miss the appeals deadline or if the IRS Office of Appeals denies your abatement as well, your only option is to pay the penalty and sue the government for refund, either in District Court or the Court of Federal Claims.

Appeals will send you Letter 1277 informing you how to file such a suit:

- Pay the penalty.

- File a claim for refund of the penalty on Form 843 with the IRS Service Center that processed the relevant tax return and include a statement requesting your claim be immediately disallowed.

- Wait to receive a formal notice of claim disallowance in the mail.

- File your suit in District Court or the Court of Federal Claims within two years of the date of this notice.

Dealing with the IRS Office of Appeals and appealing penalty rejections really deserves an entire article to it, so I will cover that in a separate article at a later time.

Reasonable Cause Penalty Abatement

If the tax year for which you are seeking penalty abatement does not qualify for first-time penalty abatement, you will need to make an argument to the IRS that the reason you did not comply with your tax obligations was for reasonable cause, meaning that despite you exercising “ordinary business care and prudence” in determining your tax obligations, you were not able to comply with them.

In choosing to grant penalty relief based on reasonable cause, the IRS instructs its employees to look at “all facts and circumstances” relevant to the taxpayer’s situation.

Examples of “all facts and circumstances” include, but are not limited to, asking questions such as the following:

- What happened that prevented you from fulfilling your tax obligations, when did this event happen, and how exactly did this event prevent you from fulfilling your tax obligations? It’s not enough to say, “Something bad happened to me!” and expect the IRS to abate your penalties. You have to show that this event — or at least the time period in which you were affected by it — was in relatively close proximity to the deadlines for fulfilling your tax obligations as well as show a strong logical connection between this event and your inability to fulfill these obligations.

- During the time period affected by this event, how did you handle your other affairs? The fact that you were able to, say, hold a demanding job, maintain a time-consuming hobby, or start a business during this time period might indicate that you were actually able to comply with your tax obligations but you simply chose not to.

- Once your circumstances changed, did you attempt to fulfill your overdue tax obligations? Remember, the IRS is going to look at every year on its own for penalty abatement. It may very well grant you penalty abatement for reasonable cause in the year that some traumatic event happened to you and perhaps even for the years during which you were in ongoing, intensive medical treatment and unable to attend to several important elements of your life. But once, say, you finished this treatment and got back into your normal rhythms of life, the IRS’s expectation would be that you would be in compliance with your current tax obligations and make some attempt to fulfill your past-due tax obligations. The IRS specifically states that “reasonable cause does not exist if, after the facts and circumstances that explain the taxpayer’s noncompliant behavior cease to exist, the taxpayer fails to comply with the tax obligation within a reasonable period of time.”

Below, I have provided you with example “reasonable causes” that the IRS provides in IRM 20.1.1.3.2. Note, however, that there may be other “reasonable causes” than those listed below.

In fact, the IRS states in this IRM that an acceptable explanation is not limited to the causes below, but in all abatements for reasonable cause, the taxpayer must have shown that they exercised “ordinary business care and prudence.”

Ordinary Business Care and Prudence

Over and over in the IRS’s guide to penalty abatement for reasonable cause, one sees this phrase: “ordinary business care and prudence”.

But what is “ordinary business care and prudence”?

The IRS defines it like this: making provisions — that is, taking a degree of care that a reasonably prudent person would exercise — for business obligations to be met when reasonably foreseeable events occur.

The IRS directs its employees to review all available information about the taxpayer’s case in determining whether they exercised ordinary business care and prudence, including these elements:

- Taxpayer’s Reason: Obviously, the taxpayer needs a reason — hence the phrase “reasonable cause” — why they were unable to comply with their tax obligations despite exercising ordinary business care and prudence. The trick, of course, is to line up this reason — both factually and chronologically — with the period of noncompliance.

- Compliance History: A taxpayer’s good compliance history won’t really help when it comes to abatement for reasonable cause, but a taxpayer’s bad compliance history may very well hurt them. The IRS’s logic is that the same noncompliance issues, happening repeatedly, may indicate that the taxpayer simply does not exercise ordinary business care and prudence in their tax dealings.

- Length of Time: The IRS instructs its employees to take into account the length of time between the event the taxpayer claims made them unable to comply with their tax obligations and the noncompliance itself. IRS employees are also to consider the length of time between the taxpayer’s noncompliance and the date they became compliant or took steps to become compliant.

- Circumstances Beyond the Taxpayer’s Control: Remember, ordinary business care and prudence involves making and executing plans to meet one’s business obligations in consideration of reasonably foreseeable events. And the fact that a taxpayer could control the timing or the very happening of a particular event very likely makes that event “reasonably foreseeable” in the eyes of the IRS. Welcoming a new baby into one’s family, starting a demanding job, and moving across the country, for example, can all be quite stress-inducing, but these are all generally events that taxpayers have control over and can reasonably foresee. Therefore, these are all things that a taxpayer has an obligation to plan around in order to meet their tax obligations. On the other hand, the sudden death of a family member, the loss of one’s home due to an electrical fire in the middle of the night, or the theft of a file containing irreplaceable tax records are events that the taxpayer had no control over and therefore may be better grounds for penalty abatement for reasonable cause.

1. Death or Serious Illness

The IRS may grant reasonable cause penalty relief if you or a member of your immediate family — spouse, sibling, parent, grandparent, or child — pass away or sustain a serious illness.

Keep in mind that a death or serious illness in the family does not automatically guarantee that the IRS will grant your penalty abatement; rather, there has to be a logical connection between the unfortunate event and your inability to meet your tax obligations.

In considering this connection, ask yourself the following questions:

- What was your relationship to the individual who became seriously ill or died? The death of a grandparent with whom you had no discernible relationship would likely not be the basis for reasonable cause.

- When did the individual pass away? If your sibling, say, passed away unexpectedly in April 2013, and as a result you entered a severe, medically-documented depression lasting the better part of a year, the IRS may view this as reasonable cause for you to not have filed your 2012 and possibly your 2013 tax returns. However, unless there are other circumstances at play, the IRS would likely not view your sibling’s death as reason for you to not have filed your 2014 and later tax returns.

- How severe was the illness? Millions of people file their tax returns every year while under the weather with the cold or even the flu; unless you were hospitalized, the IRS will likely not consider common illnesses like these as “severe” enough to be grounds for reasonable cause. On the other hand, dealing with a disease that was life-threatening or impeded your ability to function in your typical manner could be grounds for reasonable cause penalty abatement.

- How long did the illness last? Being hospitalized for a week or two and then making a full recovery shortly thereafter would likely not give you grounds for reasonable cause except perhaps if the hospitalization occurred during the tax return deadline.

- How the death / illness prevent tax compliance? That someone died, or that you or someone became ill, is not reason enough for the IRS to abate a penalty on the basis of reasonable cause. There must be some direct connection between the event and the inability to comply with one’s tax obligations.

- Were other business obligations impaired by the death / illness? If you were able to, say, continue to meet other business obligations — such as adequately maintain a full-time job, for example — during the time you were sick or after a loved one passed away, the IRS may question why you weren’t able to fulfill your tax obligations as well.

- When did you become compliant again? It generally makes for a stronger reasonable cause case if you can show that you became compliant again shortly after the event happened.

2. Unavoidable Absence

If you were unavoidably absent from your home for a long period of time — for example, if you were part of a sequestered jury — this could constitute reasonable cause for not meeting your tax obligations.

However, as with all reasonable cause cases, you would still have to show that you exercised “ordinary business care and prudence” to meet your tax obligations while you were away but were still unable to meet your tax obligations.

The Reasonable Cause Assistant (RCA)

IRS employees will generally use a computer program called the Reasonable Cause Assistant, or RCA for short, to make determinations of whether a penalty for a given year should be abated for reasonable cause.

3. Inability to Obtain Records

If you were not able to obtain your tax records, you may qualify for reasonable cause relief.

Similar to the other reasonable cause justifications, there must be some connection between your inability to obtain records and your inability to maintain your tax obligations.

In considering this connection, ask yourself the following questions:

- Why were these records needed to maintain your tax obligations? Let’s say you didn’t receive a certain tax form for the year — for example, a Form 1099-INT showing your interest income paid on a savings account. “So what?” the IRS may say. “You could have simply gone through your statements, noted the amount of interest credited to your account during the year, and reported that on your tax return.” Before you count on using the inability to obtain records as a basis for your reasonable cause, make sure you anticipate any reasons why the IRS would deny this reason as a valid cause and formulate a response to these anticipated objections.

- Why were the records unavailable? In general, the less control you have over the availability of the records, the better the situation may look for you in the IRS’s eyes. If you are a passive investor in an LLC — and the amounts reported on the K-1s are generally very significant compared to the rest of your income — and the LLC fails to supply you with your Schedule K-1 or even an estimate of the Schedule K-1 amounts despite your repeated requests, this is generally a good fact pattern since you have no control over when the LLC will provide these records to you.

- What steps did you take to secure these records? The IRS considers it “ordinary business care and prudence” for one to at least make a reasonable effort to obtain one’s tax records if they are initially unable to retrieve them. If you do not receive a tax document you were expecting, do everything you can to obtain a copy of it and make sure you document these efforts.

- When and how did you become aware that you did not have the necessary records? With many penalty abatement for reasonable cause cases, the timeline of events is crucial. If you did not become aware of your inability to obtain these records until after the original and extended tax return deadlines had already passed, the IRS is unlikely to approve your penalty abatement for reasonable cause based on inability to obtain records since in this case the lack of records was not a cause for you failing to file your tax return timely.

- Did you explore other means to secure the needed information? The more extensive your efforts to secure the records, the better your case is.

- Why did you not estimate the information on the records? Believe it or not, the IRS actually allows taxpayers to use estimated information on their returns, though they have no obligation to do so. So, knowing this, the IRS may question why you did not simply make reasonable estimates in order to comply with your tax obligations. For example, in the LLC example above, perhaps — in addition to requesting your Schedule K-1 or an estimate of your ratable share of LLC income, expenses, and other tax items — you also requested to inspect the LLC’s books and records for the previous year. Although there would obviously be tax adjustments you would need to make against the LLC’s book income, and the calculation of your ratable share may not be as simple as multiplying your ownership percentage to the LLC’s net income, nevertheless

- Did you contact the IRS for instructions on what to do about the missing information? If you did attempt to call the IRS but were unable to be connected to a live person, be sure to keep your phone records showing that you made repeated attempts to do so.

- Did you promptly comply with your tax obligations once the missing information was received? Let’s say that despite your best efforts you were unable to obtain necessary tax return information to complete your 2022 tax return for the duration of 2023, but you were able to obtain this information in early 2024. Nevertheless, you held off on filing your 2022 tax return until 2026. The IRS may grant a partial abatement for your failure-to-file penalty for the penalty attributable to the period through early 2024 and a reasonable time after that, but it would not likely grant abatement for the penalty for the penalty calculated for late 2024 through 2026.

- Do you have supporting documentation showing your efforts to get the needed information? It’s one thing to say to the IRS that you exerted your best efforts in an attempt to obtain the necessary documentation, in which case they will say, “Prove it.” And the more documentation you are able to submit to the IRS to show them that you exerted your best efforts in an attempt to obtain the necessary documentation, the stronger your penalty abatement claim will be.

Multiple Reasonable Causes

Sometimes, there may be some intersectionality among various reasonable cause types.

For example, if you were unable to obtain your records — which is potentially a reasonable cause in and of itself — because you were hospitalized with a serious illness (see preceding section) because you were the victim of a house fire (see next section), you have multiple reasonable causes to cite in your penalty abatement request.

4. Disasters and Other Disturbances

If you or your business experienced a significant disturbance due to some disaster beyond your control such as a fire, casualty, natural disaster, or some other catastrophe, this may allow you to seek penalty abatement for reasonable cause.

Of course, there has to be some direct connection between the disturbance and your inability to meet your tax obligations.

In consider this connection, ask yourself these questions:

- What was the effect of the disturbance on your life and business? The mere fact that, say, there was a fire in your home would not qualify you for penalty abatement based on reasonable cause. For example, if you experienced a fire in your home, but it was quickly put out, it did not displace you, and you were able to continue with your other affairs with relative ease, the IRS probably wouldn’t accept this fire as grounds for reasonable cause. However, if your home was destroyed, and you were displaced, and most aspects of your life and business were put on hold as a result, the IRS may consider this grounds for reasonable cause abatement.

- What steps did you take to comply? Even if the disturbance ultimately made it impossible or unreasonably difficult for you to comply with your tax obligations, did you at least expend some efforts to comply? Doing so helps your case with the IRS.

- Did you comply when it became possible to do so? Similar to hospitalizations and other misfortunes, it is a good fact pattern for your case if you could show that you were able to comply as soon as you were able to.

- When did the disturbance take place? Even if a fire burned down your home, you were displaced, and your life and business were put on hold for, say, two years, this would not be a reasonable cause basis for why you were unable to comply with your tax filing obligations for, say, five whole years after the fire, assuming that life resumed some normalcy after the initial two years.

Federal Disaster Areas

If you are an affected taxpayer in a federally-declared disaster area, you may be eligible for special penalty relief!

5. Reliance on Erroneous Advice

While taking erroneous tax advice from your barber wouldn’t be grounds for penalty abatement for reasonable cause — a reasonable taxpayer, after all, wouldn’t trust that their barber knows what he or she is talking about when it comes to taxes — relying on erroneous advice from your tax professional or the IRS could possibly be grounds for abatement.

Also, the more specific the advice you received as to your individual situation, the more reasonable it would be for you to rely on this advice.

For example, going to a seminar where a CPA talked about some aggressive tax positions he or she took on a client’s tax return is not advice provided for your individual situation.

But let’s say you directly ask your CPA (or the IRS, for that matter) a tax question in which you lay out all the facts accurately and you then receive advice from your CPA pertaining to this tax question that results in you being assessed a penalty — this is likely an example of reasonable reliance.

In fact, the Internal Revenue Manual directly states that, in general:

“If the taxpayer…provided the IRS or the tax professional with adequate and accurate information, the taxpayer is entitled to penalty relief for the period during which he or she relied on the advice.”

If, however, you receive notice that the advice is no longer correct or no longer represents the IRS’s position, you are no longer entitled to penalty relief on the grounds of reliance on erroneous advice from that day forward.

While “receiving notice” would obviously include a direct communication with you, the IRS could likely argue that other events that occurred after you received the advice — for example, new legislation or regulations, a United States Supreme Court decision, or some public announcement by the IRS — could also constitute sufficient notice for you to know that you can no longer rely on the previously-received advice.

Also keep in mind that you can’t get advice after you already filed your tax return and claim that you relied on this advice when you were preparing your return — but obviously you could potentially qualify for abatement if you amend your tax return on the basis of erroneous advice you received after you filed your original tax return.

There is also the question of the level of complexity as well; in my experience, the IRS will generally only grant relief of a penalty for reliance on the erroneous advice of a taxpayer when the issue at hand is considered technical or complicated.

Not a Get-Out-of-Penalty Free Card...

Like every other potential reasonable cause, the fact that you relied on a tax professional or the IRS for advice is not a guarantee that your penalty will be abated.

It’s not enough to show that your penalty was the result of pursuing some action based on reliance on erroneous advice; you must also show, based on all facts and circumstances, that you exercised ordinary business care and prudence in relying on this advice.

Can I Blame My Accountant If My Taxes Weren’t Filed?

While you can’t blame your accountant, lawyer, or other professional for not filing your tax return or paying your taxes on your behalf — those are responsibilities that cannot be delegated — you may have a basis for reasonable cause if:

- Your tax professional explicitly told you that you did not have a filing or payment requirement and you relied on their advice.

- Your tax professional had access to your tax records that were necessary for you to comply with your tax obligation and did not give them to you in time to comply.

- You trusted your tax professional to keep you in compliance with any new tax laws, the professional failed to do that, and you could not have been reasonably expected to know about this change yourself (see “Ignorance of the Law”, below).

Penalty Relief Under § 6404(f)

Internal Revenue Code § 6404(f) specifically states that the IRS must abate any penalty directly attributable to erroneous written advice from an officer or employee of the IRS acting in their official capacity, that is, in the course of their employment insofar as:

- The taxpayer reasonably relied on this erroneous written advice and it advice was in response to a specific written request from the taxpayer.

- The taxpayer provided adequate and accurate information to the IRS in obtaining this written advice.

So the standards are rather high and exceptional to qualify for relief under § 6404(f), but of course even if the taxpayer’s situation does not meet these standards, the taxpayer may still be able to obtain penalty relief if they can demonstrate that they exercised ordinary business care and prudence in relying on the IRS’s written advice.

Note that in many cases, the IRS has extended § 6404(f) relief to cases involving erroneous oral advice, but it may push back in certain circumstances, such as:

- While an IRS employee may have given the taxpayer erroneous advice, the IRS did have correct information about the issue in various publications, tax form instructions, etc.

- The taxpayer did not keep adequate supporting documentation of their conversation with the IRS in which the erroneous advice was obtained. Good supporting documentation would include a notation of the taxpayer’s question to the IRS, documentation of the advice provided by the IRS, the date of the conversation, and the name of the IRS employee who provided the erroneous advice.

6. Mistake Was Made

No, you can’t expect the IRS to grant you penalty abatement for reasonable cause simply because you made a mistake.

In fact, the IRS explicitly states that making a mistake is “generally…not in keeping with the ordinary business care and prudence standard and does not provide a basis for reasonable cause” (emphasis in original).

That said, the IRS says that the reason the taxpayer made a mistake may be a factor that IRS employees should consider in light of additional facts and circumstances showing the taxpayer exercised ordinary business care and prudence but nevertheless was unable to meet their tax obligations.

Factors such as when and how you became aware of the mistake, whether you fully or at least partially corrected or attempted to correct the mistake, and whether you delegated the duty to a subordinate — as well as your relationship with this subordinate — are all contributing factors here as well.

7. Ignorance of the Law

Given that exercising ordinary business care and prudence means making reasonable efforts to determine one’s tax obligations, ignorance of the tax law is not enough to obtain penalty abatement for reasonable cause; there must be other facts and circumstances to give merit to a taxpayer’s claim involving ignorance of the law.

Here are some questions to ask as you put together your reasonable cause penalty abatement because you honestly did not know what your tax obligations were:

- How complicated was the tax issue? It’s fairly common knowledge that people have to file a tax return in the United States; good luck trying to get a penalty abated under the claim that you didn’t know you had to file a tax return. That said, we were able to get a penalty abated for reasonable cause for a client who had recently retired whose tax professional told him that he did not have to file because his only income was Social Security benefits and municipal bond interest income.

- Were you previously in compliance regarding this issue? It’s not a good fact pattern if you were previously in compliance regarding the tax issue and then claim that you somehow forgot about your obligation in a future tax year.

- Were you previously penalized by the IRS for this issue? Since the IRS typically sends a notice to a taxpayer when it penalizes them for missing tax obligations — and this notice will typically inform the taxpayer of their tax obligations in a degree of detail — it’s an especially bad fact pattern if you have been previously penalized for not complying with a particular tax obligation and even so continue to fail to comply with it in the future.

- What is your level of education and sophistication? The IRS may simply be more forgiving of someone with minimal education being unaware of a particular tax obligation than someone with a college or some other advanced agree. It’s an especially bad look if you have some connection with the fields of finance and accounting — and especially taxes — and yet you failed to meet your tax obligations. That said, don’t be afraid to push back on the IRS’s claims that based on your high level of education you should have known about your tax obligation; in my opinion, it’s not reasonable for them to assume that just because you have, say, a Ph.D. in Electrical Engineering that you should be well-acquainted with the intricacies of the Internal Revenue Code.

- Is this a new obligation based on recent changes in tax forms or law? In general, the newer the tax obligation that you missed, the better your chances of obtaining penalty abatement for reasonable cause based on not knowing about this obligation.

- Did you at least make some effort to comply with the law? Maybe you didn’t fully understand the law enough that you could fully comply with your tax obligation, but did you at least make some effort to make the IRS aware of your situation or pay the tax that you thought to be due?

Statutory and Regulatory Exceptions

Sometimes, specific sections of the Internal Revenue Code or the Treasury Regulations provide for exceptions to otherwise-assessable penalties.

For example, IRC §6654(d) states that, in general, taxpayers must make estimated tax payments in four equal installments throughout the year and that the amount of these payments should either be:

- 90% of the current year’s tax liability at any income level, or

- 100% of the preceding tax year’s tax liability for taxpayers whose adjusted gross income on their previous year’s tax return was $150,000 or less ($75,000 or less for married individuals filing separately), or

- 110% of the preceding tax year’s tax liability for taxpayers whose adjusted gross income on their previous year’s tax return was greater than $150,000 ($75,000 for married individuals filing separately).

However, IRC §6654(e) provides statutory exceptions to the estimated tax penalty in any of the following circumstances:

- The taxpayer’s tax liability, after accounting for wage withholding, is less than $1,000.

- The taxpayer had no tax liability in the preceding tax year.

- The IRS determines that the estimated tax penalty would be against equity and good conscience because the taxpayer was affected by a casualty, disaster, or other unusual circumstance.

- The taxpayer retired and is at least 62 years old or the taxpayer became disabled in the year in question.

Since these exceptions are penalty-specific, we will not discuss them in this article but will rather discuss these exceptions in articles about these specific penalties themselves.

Administrative Waivers

Once in a while, the IRS may announce that they are providing administrative relief from an otherwise-assessable penalty.

These announcements are known as administrative waivers and can be announced in policy statements, news releases, or other formal communications from the IRS.

These waivers are typically temporary and apply to specific penalties for specific time periods.

For example, if the IRS is delayed in printing or mailing tax forms pertaining to a specific tax issue or in publishing guidance — such as Treasury Regulations — pertaining to a specific tax issue, it may provide for an administrative waiver for delayed compliance with respect to that specific tax issue.

The most common form of administrative waiver is the first-time penalty abatement discussed previously. Since first-time penalty abatement is so popular, it has been discussed at length above.

Another recent administrative waiver is the automatic abatement of the failure-to-file penalty recently announced by the IRS in Notice 2022-36. Under this notice, the IRS automatically forgave the failure-to-file penalties on the following returns:

- Certain income tax returns including Forms 1040, 1041, 1065, 1066, 1120, 1120S, 990-T, and 990-PF for tax years 2019 and 2020 as long as they are filed on or before September 30, 2022.

- Certain international information returns including Forms 5471, 5472, 3520, and 3520-A for tax years 2019 and 2020 as long as they are filed on or before September 30, 2022.

- Certain information returns — such as in the Form 1099 series — for tax year 2019 as long as they were filed by August 3, 2020.

- Certain information returns — such as in the Form 1099 series — for tax year 2020 as long as they were filed by August 2, 2021.

Undue Hardship

If you can prove to the IRS that you exercised ordinary business care and prudence to provide for your tax liability, but yet you were nevertheless unable to pay your taxes on time, the IRS may grant you penalty relief for the failure-to-pay penalty.

That said, simply the fact that you were unable to pay your taxes on time does not, in and of itself, provide a basis for this sort of relief; you could very well have spent money on unnecessary expenses that could have otherwise gone to your tax liability.

For example, a good fact pattern for relief would be that you had set aside the money to pay the taxes by the due date, but due to unforeseen circumstances, you were unable to pay the taxes because paying the taxes would have resulted in undue financial hardship.

IRS Errors

If you (1) complied with your tax obligations, (2) the IRS did not recognize that you complied with your tax obligations, and (3) as a result of this non-recognition the IRS assessed a penalty on your account, you will likely be able to get this penalty abated upon request.

Examples of IRS errors that we’ve seen include:

- Making an erroneous computation or assessment of tax

- Not crediting a taxpayer’s accounts for a payment made or crediting the wrong tax period

- Mathematical error

- Not posting a validly-submitted extension request

When You and the IRS Disagree

It’s inevitable that some taxpayers will disagree with the IRS regarding their penalty assessment.

Thankfully, there are some solutions in place that can help to resolve these disagreements.

Manager Conference

If you and an IRS employee cannot reach an agreement, consider elevating the discussion to the employee’s immediate manager.

Theoretically, the employee’s manager has more knowledge of the IRS’s rules regarding penalty assessment and abatement as well as more experience in working with taxpayers who want to arrive at a resolution of their situation.

Taxpayer Advocate Service

If your disagreement with the IRS regarding your penalty abatement case meets certain criteria and the IRS cannot resolve your issue within 24 hours, they are instructed to refer your case to the Taxpayer Advocate Service (TAS) using Form 911 if you so request.

TAS is an independent organization within the IRS that describes itself as taxpayers’ “voice at the IRS”.

Essentially, their job is to step in when the IRS isn’t doing what the IRS is supposed to do. A common example of this is when the IRS is not following their own policy and procedures as set forth in the Internal Revenue Manual.

The Internal Revenue Manual section on penalty abatement has this to say about TAS:

“The purpose of TAS is to give taxpayers someone to speak for them within the IRS — an advocate. An advocate conducts and independent and impartial analysis of all information relevant to the taxpayer’s problem. TAS guarantees that taxpayers will have someone to make sure their rights are protected and someone to turn to when the system is not responsive to their needs.”

You can also initiate TAS intervention by reaching out to your local taxpayer advocate.

Appeals

The IRS Independent Office of Appeals (“Appeals”) is another independent body within the IRS, and it is your right as a taxpayer right to challenge the IRS’s assessment of a penalty against you.

You may appeal a penalty either before or after it is assessed and, if assessed, either before or after it is paid.

Unlike the IRS compliance and collection divisions, Appeals also has the authority to settle penalties for less than the full amount owed due to the hazards of litigation, namely the cost of going to court to contest the issue.

Court

Another avenue of appealing penalties is by filing a petition in the United States Tax Court — this may be done without paying the penalties beforehand — or by paying the penalties the IRS claims are owed and filing suit in United States District Court or the United States Court of Federal Claims.

IRS Penalty Abatement FAQs

Can I get IRS interest abated?

Yes, you can get IRS interest abated in some circumstances.

For example, if you successfully get an IRS penalty abated, the interest on that penalty will be abated as well.

You may also be able to get IRS interest abated if you can show that the IRS made a mistake pertaining to the assessment of a tax on which interest was calculated.

What if I simply forget to meet my tax obligation?

Unfortunately, simply forgetting to meet your tax obligations will not qualify you for penalty relief under reasonable cause.

Here is what the IRS says about forgetfulness in Internal Revenue Manual § 20.1.1.3.2.2.7(1):

“The taxpayer may try to establish reasonable cause by claiming forgetfulness or an oversight by the taxpayer, or another party, caused the noncompliance. Generally, this is not in keeping with the ordinary business care and prudence standard and does not provide a basis for reasonable cause.”

What if my accountant forgot to file my taxes?

Unfortunately, the IRS is very clear that a taxpayer cannot delegate the responsibility to file one’s tax return to another party, even if that other person is a tax professional who has been paid in advance by the taxpayer to perform such duty.

Here is what the IRS says in Internal Revenue Manual § 20.1.1.3.2.2.7(2) concerning forgetfulness and oversights:

“Relying on another person to perform a required act is generally not sufficient for establishing reasonable cause. It is the taxpayer’s responsibility to file a timely return and to make timely deposits or payments. This responsibility cannot be delegated.”

Can you get IRS penalty abatement if you already paid the penalty?

Yes, you can get IRS penalty abatement if you already paid the penalty.

Paying the penalty does not forfeit your right to contest that penalty later.

So if you’ve already paid an IRS penalty that you think you have grounds to contest, contest it.

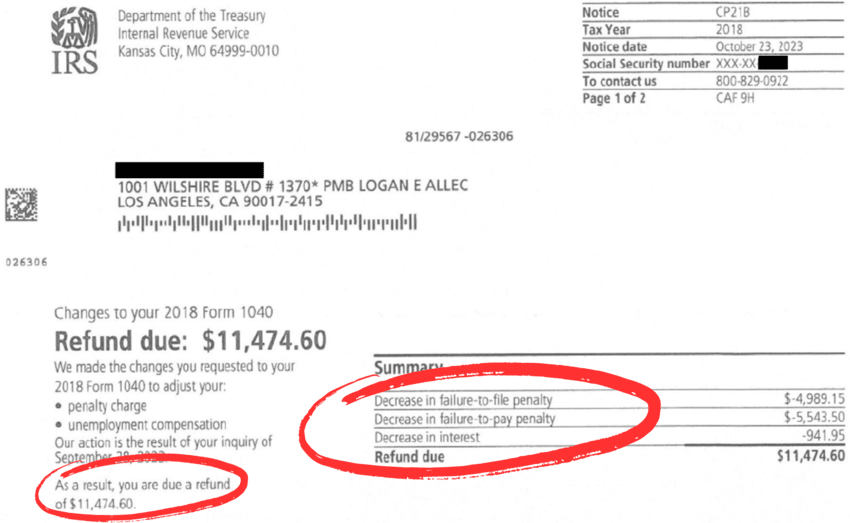

We recently (in October 2023) convinced the IRS to abate a penalty for our client for tax year 2018 in the amount of $10,532.65, along with interest on that penalty of $941.95 — so a total win for the taxpayer of $11,474.60.

This taxpayer had already paid this penalty and interest, so what happened when we got the penalty abatement through?

The IRS sent her a Notice CP21B notifying her of our win on her penalty and interest, and in that notice the IRS told her, “As a result [of the reduction in penalty and interest], you are due a refund of $11,474.60,” and a few weeks later she got that refund check.

We did a lot of other things for her as well beyond this, but getting an $11,000 check from the government was a nice cherry on top for her at the close of her case.