How to Negotiate With the IRS: Back Tax Negotiations Explained by a CPA

Is it possible to negotiate with the IRS? Will the IRS settle for less?

The answer is, surprisingly, “Yes!”

However, negotiating with the IRS is probably unlike any other negotiation you’ve participated in before.

Unlike when you negotiate with, say, a car salesperson or when you haggle at your local flea market (or swap meet, as it were), negotiating with the IRS generally involves a formalized process involving procedures and forms at least at first.

Once you go through those procedures and submit the appropriate forms and someone at the IRS is assigned to your case, then there’s more human-to-human interaction.

But in order to get to that point, you have to jump through some hoops.

Table of Contents

The IRS’s Negotiating Playbook

But there is also something really cool about negotiating with the IRS that you can work to your immense advantage, and that is that the IRS makes their negotiating playbook completely public and available for free.

That’s right — it’s called the Internal Revenue Manual, and it’s available for you to read and study right at irs.gov/irm. And of particular interest to most reading this, I’m sure, are Part 5 of the IRM — which has to do with the IRS’s process for collecting taxes from taxpayers, and this includes in Section 5.8 the offer in compromise procedures, which is the IRS settlement program — as well as Part 20 of the IRM, which has to do with IRS penalties and interest.

And the more familiar you are with the Internal Revenue Manual, which is the IRS’s negotiating playbook, the more successful you will be at IRS negotiations. But the flip side to that is that if you are not familiar with the Internal Revenue Manual and how the IRS negotiates things, you will get steamrolled.

And really in my content — including this very article — a lot of what I’m doing is simply explaining parts of the Internal Revenue Manual in an easy to understand way.

So in this article, I’m going to tell you why the IRS lets you negotiate with it, what you can negotiate with the IRS, and finally exactly how to negotiate with the IRS.

So first, let’s talk about why the IRS lets you negotiate with it.

Why Does the IRS Negotiate?

The IRS is the nation’s most powerful collection agency; unlike other creditors, the IRS does not need to get a judgment against you in order to start garnishing your wages or levying your bank accounts. You don’t even need to file a tax return for the IRS to take such action; it can file a tax return for you — called a substitute for return (SFR) — and assess and collect tax based on that SFR.

Like I said, the IRS can take your wages, drain your bank account, and unlike most other creditors they can even take some of your Social Security benefits; the Internal Revenue Service is a force to be reckoned with when it comes to getting what it believes is owed to it.

And not only that, the IRS has criminal law on its side as well; Internal Revenue Code Section 7203 says that if you don’t file your taxes or pay your taxes, that’s a federal crime punishable by fines and imprisonment.

So why on earth would an organization that can simply send a notice to a taxpayer’s human resources or payroll department saying, “Don’t pay your employee any more; pay us,” be willing to negotiate with those who owe it money?

Why would an organization that can show up with armed officials from the IRS Criminal Investigation Division and arrest you and press charges against you and whose attorneys in the IRS Office of Chief Counsel have a very high conviction rate in the matters that it does choose to prosecute — why would this organization let taxpayers come to it for a negotiation?

Here’s why: Like everything else the IRS does, the IRS lets you negotiate with it because doing so is in the IRS’s best interest.

The IRS it not a charitable organization, so don’t approach IRS negotiations as some groveling thing. The IRS does not reach settlements with taxpayers out of the goodness of its heart, for the most part. There are things called effective tax administration offers in compromise that are the closest thing to that, but those are fairly rare and far and few between.

The reality is that negotiating with taxpayers is a win-win. It’s obviously a win for taxpayers who owe the IRS in that they can get more time to pay their taxes off or maybe even get some of their tax debt forgiven, but you also need to understand — because this will frame the way you negotiate with the IRS — is that negotiating with taxpayers is also a win for the IRS in three ways.

Reason #1: Better Publicity

Could you imagine what would happen in the United States if for everybody who gets behind on filing their taxes or paying their taxes or both the IRS sends armed agents in, has them arrested, and seizes their property?

That probably wouldn’t go over very well, and if that were to happen, we would very likely see revolts and possibly revolution.

So the IRS has this mindset as an organization to achieve this balance between letting the public at large know that it is a very powerful collection organization with awesome powers to assess and collect taxes and also letting the public know that despite its powers it can be reasoned with.

And by negotiating with taxpayers not only what they owe but how long they have to pay what they owe, the IRS moves closer to achieving this balance.

Don’t get me wrong; the IRS will push people around when they want to; but for the majority of taxpayers, the IRS plays a lot nicer than it could. And that is strategic; we have a voluntary tax system; and it is in the IRS’s best interest to maintain a good reputation among the general public or at least not maintain a reputation of an organization that bulldozes everything in its path.

Reason #2: Increased Collections

If the IRS didn’t negotiate with taxpayers and if you owed the IRS your choice was either to pay what you owe immediately or face the full wrath of the IRS, we would see a lot more people going under the radar (possibly overseas) and simply not paying the IRS again.

But that would be bad for the IRS in the long run, and it knows that getting something from a taxpayer is better than getting nothing.

But if the game were all or nothing and the IRS absolutely did not negotiate with taxpayers, the IRS would be getting nothing in a lot of cases because taxpayers would simply go off the grid.

So it is in the IRS’s best interest to communicate to these taxpayers that owe them, “Let’s make a deal.”

Reason #3: Increased Compliance

Oftentimes, part of the deal when you negotiate with the IRS is that you have to remain in compliance.

For example, with an offer in compromise, a taxpayer has to remain in compliance with the filing of all tax returns and payment of all taxes due for five years from the date their offer in compromise is accepted by the IRS.

So by engaging in these negotiations and structuring some of these agreements and settlements in a particular way, the IRS can take somebody who is out of compliance and owes them a lot of money and by reaching an agreement with them turning them into a good little taxpayer going forward.

What Can You Negotiate With the IRS?

Now, before we begin, you need to know what you can actually negotiate with the IRS.

You can negotiate three things with the IRS:

- What you owe

- What you’ll pay

- How long you have to pay

1. What You Owe

You can negotiate what you owe the IRS — in other words, your liability.

The two most common ways this is done, in practice, is by filing a return to replace an SFR prepared by the IRS or by negotiating a full or partial abatement of the penalties the IRS has charged to your account.

Replacing an SFR

If you don’t file a tax return and the IRS believes you should have filed a tax return, the IRS may file a tax return for you. This is called an SFR (or substitute for return).

Based on this SFR, the IRS assesses your tax liability and beings collection activities.

However, if you file your missing tax return for this year, you can replace your SFR liability with the liability shown on your filed tax return — which is generally lower than the liability shown on the SFR — effectively “negotiating” your tax liability with the IRS.

Learn more about SFRs in this article.

Penalty Abatement

The other major way you can negotiate your tax liability with the IRS is by requesting that the IRS reduce or eliminate the penalties it has charged to your account.

There are over 150 different penalties the IRS can assess, but the most common penalties are the failure-to-file penalty and the failure-to-pay penalty.

As it sounds, the failure-to-file penalty is the penalty the IRS assesses when a taxpayer files their return late. The amount of the failure-to-file penalty is 5% of the tax due shown on the return for every month or part of a month the return is late, up to a maximum of 25%.

The failure-to-pay penalty is the penalty the IRS assesses when a taxpayer pays their taxes late — typically after the original (not extended) due date of their tax return, which is typically April 15. The amount of the failure-to-pay penalty is 0.5% of the tax due shown on the return for every month or part of a month the tax remains unpaid, up to a maximum of 25%.

The failure-to-file penalty and the failure-to-pay penalty can run concurrently, but for every month for which a taxpayer is liable for both the failure-to-file and the failure-to-pay penalties, the failure-to-file penalty is reduced by the failure-to-pay penalty so the maximum combined penalty for these months is 5% per month.

The maximum combined failure-to-file penalty and failure-to-pay penalty is therefore 47.5%.

The good news, however, is that the IRS is sometimes willing to negotiate these penalties through a process known as penalty abatement.

Learn more about IRS penalty abatement in this article.

2. What You’ll Pay

In addition to negotiating what you owe to the IRS — your liability — you can also negotiate how much of that liability the IRS should require you to pay.

This is known as negotiating your collectibility, and this is where the tax relief options that we provide really kick in.

The three most popular ways to negotiate what you’ll pay to the IRS are:

- Offer in Compromise

- Partial-Payment Installment Agreement

- Currently Not Collectible Status

Offer in Compromise

An offer in compromise is an agreement with the government to settle your tax debt for less than you owe.

However, most taxpayers do not qualify for an offer in compromise.

Want to learn more? Read my article on the offer in compromise formula.

Partial-Payment Installment Agreement

A partial-payment installment agreement (PPIA) is an agreement with the government to pay the IRS less than you owe in an installment agreement.

Although more taxpayers qualify for PPIAs than offers in compromise, not all taxpayers can successfully negotiate a PPIA with the IRS.

Similar to an offer in compromise, the starting point for PPIA negotiations is mathematical: You must prove to the IRS that your monthly disposable income is low enough that even if you paid all of it to the IRS every month, the sum total of the payments you make before your tax debt drops off would not exceed your total liability.

However, the IRS can revisit this arrangement every couple years, and if they believe you are in a better financial situation than you were in when you entered into the PPIA, they could revise the terms.

Want to learn more? Read my article on partial-payment installment agreements.

Currently Not Collectible Status

Currently not collectible (CNC) status is a special status taxpayers can enter into with the government to not make any payments on their tax debt.

Note, however, that CNC status is technically a temporary status; similar to PPIAs, the IRS can periodically review taxpayers in CNC status and renegotiate the arrangement.

Want to learn more? Read my article on currently not collectible status.

3. How Long You Can Have to Pay

Finally, even if you aren’t successful in negotiating how much you owe to the IRS or how much you have to pay to the IRS, you can still negotiate how long you have to pay your IRS balance.

This can be done through arranging a full-payment installment agreement with the IRS.

If you owe the IRS $50,000 or less in assessed taxes, penalties, and interest, you can set one of these agreements up online at irs.gov/opa.

How to Negotiate With the IRS

Now that you know what you can negotiate with the IRS, here’s the step-by-step process of how you can negotiate with the IRS.

Step 1: Understand your starting position.

It’s not fair, but when you’re negotiating tax debt with the federal government, you’re starting in the hole.

And that hole is the amount of tax debt, penalties, and interest that the IRS believes you owe it.

That is the starting point for your negotiations. Whether you like it or not, that’s the way it is.

If you’re not sure what this amount is, find out. You’re not going to get very far negotiating with the IRS if you don’t even know what you’re negotiating in the first place.

Probably the easiest way to figure out how much the IRS thinks you owe it is to go online.

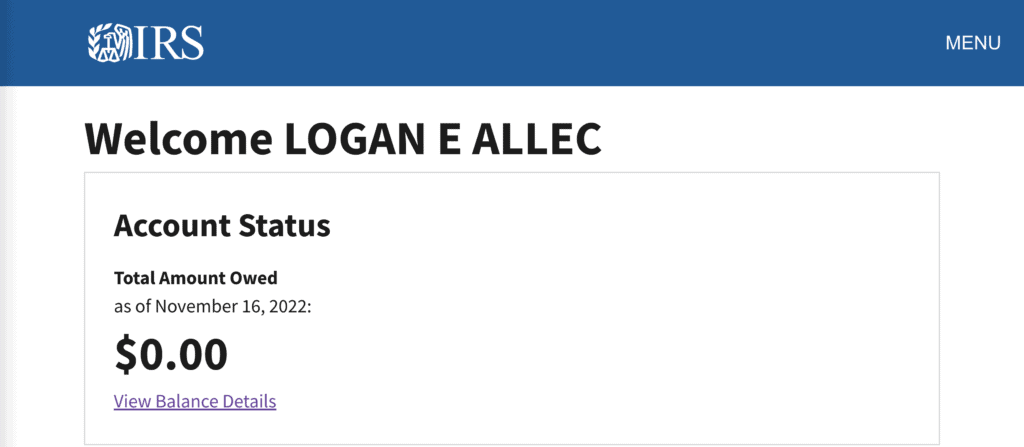

You can set up a free IRS account at irs.gov/payments/your-online-account, and once you log into your account, the first thing you’ll see is big letters that say “Welcome” and then your name and below that a box indicating your account balance with the IRS.

I can’t show you this stuff for my clients, but here’s an example from my own personal IRS account:

So right there is where you will see the amount that the IRS believes you owe it.

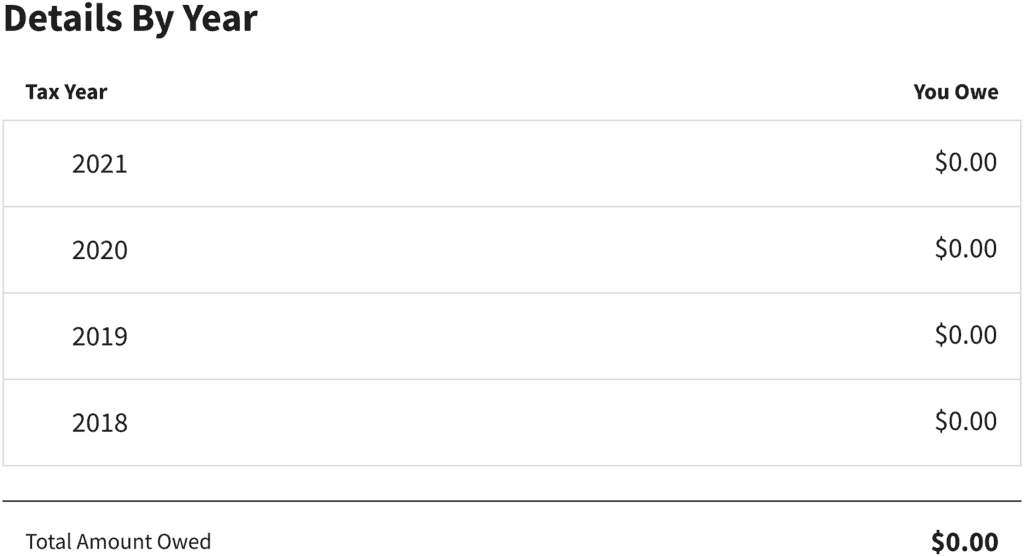

And you also want to know how much the IRS thinks you owe by year, and you can get this information by clicking “View Balance Details”.

Now, your account transcript will actually have more information on it than what will appear here — when we’re analyzing a case, we work from account transcripts — so if you can pull your account transcripts from your irs.gov account, that would be even better.

Now, it’s possible that you won’t be able to pull all your account transcripts from your IRS account, and in this case you can request those transcripts using Form 4506-T.

Step 2: Go for the low-hanging fruit.

Now, before we talk about offers in compromise, which are difficult to get, and before we talk about anything else, go for the low-hanging fruit.

In IRS negotiations, the lowest-hanging fruit is really these two things:

- IRS Errors: Review the IRS’s record on you closely. You can see some of this in your online account, but you’ll get a better view in your account transcripts. Compare the IRS’s records to your own especially regarding payments and tax return filing dates and if you see any errors, call the IRS because it could save you some money.

- First-Time Penalty Abatement: This is a break the IRS gives you on the failure-to-pay penalty and the failure-to-file penalty if you have a clean compliance history at least for the preceding three years, and it never hurts to ask for it; the worst the IRS can do is say, “No.”

- SFR Correction: If the IRS has filed SFRs for you for your 1099 income — and they won’t give you any business or itemized deductions, by the way — an easy win is to file actual returns to correct these SFRs.

So those are the lowest-hanging fruit; you may want to pursue penalty abatement for reasonable cause if you have a good reason why you didn’t file or pay your taxes late; but at this point I really want to discuss with negotiating your collectibility with the IRS.

Like I said, you can negotiate your liability, but that’s a bit more self-explanatory — you either get penalty abatement or correct your SFRs with actual returns.

So for our purposes here, we’re going to assume your liability has been fixed with the IRS and there’s no dispute there and now you want to basically negotiate with the IRS to pay less than you owe.

Step 3: Know your numbers.

At this stage, IRS negotiation is all about your numbers.

If you owe the IRS $10,000 and you have millions of dollars in accessible, liquid assets and you earn a good income, the IRS isn’t going to negotiate with you on that debt; you’re going to have to pay it all.

But on the other hand, if you owe the IRS millions of dollars and all you have is $10,000 and you don’t make a lot of money right now and you probably will not make much money for the rest of your life, you’re in a good position to negotiate a settlement with the IRS for a lot less than you owe.

So the fewer assets you have and the lower your net disposable income after your necessary living expenses are paid for, the more you can ask for in a negotiation with the IRS because the IRS cannot collect from you if it’s going to cause you hardship as determined by their own rules.

But it starts with your numbers. So what you should do is put together for yourself personally what we would call for a business two things:

- A monthly profit and loss statement: This is a listing of all your items of income you make during the month (taxable or not) minus all the expenses you have on a monthly basis to sustain your life. And if this varies somewhat from month to month, try to average this. There are other strategies that a professional could implement, but just to get a ballpark, figure out some average of your income and expenses on a monthly basis.

- A balance sheet: This is a listing of all your assets —what you own — as well as your liabilities — what you owe.

Step 4: Look at your numbers like the IRS does.

Now, you may look at your monthly profit and loss and you may be in the negative every month in reality, living off credit cards.

And based off that, you may think, “Wow, I have nothing left to pay the IRS at the end of the month; surely they will recognize that and cut me a deal.”

But that’s not how the IRS is going to view your figures.

And if you are going to negotiate with the IRS, you will need to view your numbers through their lens — through the lens of the Internal Revenue Manual.

See, the IRS has what is called national standards. These are standard amounts at which the IRS limits some of your expenses.

For example, the IRS lets you deduct your vehicle operating expenses from your monthly income in figuring your net disposable income per the IRS’s math. So this includes expenses like gas, car insurance, maintenance, repairs, and all the costs it takes to run your vehicle every month. This does not include ownership costs, by the way, such as your monthly payment on your car — that’s separate.

But let’s say your monthly operating expenses for your car add up to $500 per month. Well, I have some news for you. In general, the IRS isn’t going to let you apply that entire $500 per month against your monthly income in figuring what your disposable income is.

They will look at where you live and based on where you live they will look at the IRS Local Standards for Vehicle Operating Costs table, and for example if you live in Boston, they will only let you take $304 instead of $500 against your monthly income. And these amounts change every year, by the way — the IRS comes up with new standards every year.

And they generally won’t let you count your credit card payments against your monthly income or your kids’ private school. There are a lot of expenses they will cap or disallow, and you have to know how to work these numbers and even make changes to your financial situation to optimize it for IRS negotiations.

The vehicle operating expenses is just one example — I actually did a deep dive into how the IRS caps these expenses through its national standards in my article on the offer in compromise formula.

So if you want a deeper dive into this step, be sure to read that article.

Step 5: Get what you want.

Now, the most powerful tool you have in negotiating with the IRS is your numbers — your numbers calculated in a way that is as favorable to you as possible while still within the guidelines of the Internal Revenue Manual.

And once you have those figures — your net equity in assets and your net monthly disposable income — you’re ready to go to work and you’re ready to tell the IRS what you want.

For example, based on the IRS offer in compromise formula, if you have no net disposable income based on the IRS’s math and standards and you only have $5,000 net equity in assets based on the IRS’s math, you can push for a $5,000 settlement on your tax debt. I don’t care if you owe $5,000,000 — if you’ve done the math and you understand where the IRS is negotiating from, and you know that based on their own negotiating guide, the Internal Revenue Manual, all they can ask for is $5,000, that is what you need to negotiate.

Do not let them push you around; be aggressive. And be aggressive when doing the math too — I recently wrote an article on how actor Charlie Sheen got an offer in compromise approved.

And one thing that I admired about Charlie Sheen’s CPA in that case is 1) how aggressive he was with his initial offer of somewhere around $1.2 million on Charlie Sheen’s $7 million tax debt and 2) how he relentlessly pointed the IRS official he was working with back to the IRM. Long story short, Charlie Sheen’s offer in compromise was originally rejected by an offer examiner named Miss Earl. And according to documents in Charlie’s case, Charlie’s CPA “wrote a very comprehensive rebuttal of Miss Earl’s own detailed analysis of her view of [Charlie’s] reasonable collection potential, [and] it was this six-page, comprehensive memorandum that served as the ‘working document’ for the intensive negotiations that followed during the CDP hearing…[And] as each issue was fully discussed and addressed, [Charlie’s CPA] became aware that the appeals settlement officer was annotating and referencing this document to the applicable sections of the Internal Revenue Manual to support each and every concession that was made by the settlement officer — when convinced to make any concession — and conversely, to notate any concession made by [Charlie’s CPA].”

Know your position, tie it to the Internal Revenue Manual, defend it well, don’t give up, and get what you want.