How to Fight the IRS and Win in 10 Steps

When people talk about “fighting the IRS,” they generally have in mind one of two different situations or possibly a third:

- Situation #1: Your tax liability is in question — meaning that the IRS believes you owe more in taxes than you think you do. In this case, you are fighting the IRS over the amount you owe: You are fighting over your liability.

- Situation #2: Your tax liability is not in question — meaning that both you and the IRS agree that you owe a certain amount of tax — but you want to get the IRS off your back and possibly get some of your tax debt forgiven or at least be allowed to pay it on a schedule rather than all at once. In this case, you are fighting the IRS over how much you can afford to pay or at least how much you can afford to pay right now: You are fighting over your collectibility.

- Situation #3: Not only do you think that the IRS believes you owe them too much money, you also don’t think you shouldn’t have to pay them the full amount you think you owe them or that at least you shouldn’t have to pay it all right now. You are fighting both your liability and your collectibility.

And you can use the system below to fight the IRS and win in all of these scenarios — it’s just that with Scenario #1, you can stop at step seven, but if you’re in Scenario #2 or Scenario #3, you should go through all the steps.

Table of Contents

Step 1: Know What Winning Is

Obviously, when you’re fighting the IRS, we’re not talking about a deathmatch where one of you survives and the other doesn’t.

When we’re talking about fighting the IRS, we’re talking about getting yourself in the most advantageous position possible with the IRS, which generally means paying the least amount of money you legally can to them.

So as a first step, you need to establish for yourself your goal. I’m going to get into the technical resolution options later in this article, but as a first step here, think up — in your own words — where you want to be with the IRS at the end of this battle. For example:

- Is your goal here to simply get the IRS off your back to stop garnishing your wages and draining your bank account while you get some time to get the money together to pay them off or work out some kind of pay-over-time plan?

- Do you want to actually settle your debt with the IRS for less than you owe?

- Do you want to eliminate penalties on your account as much as you can?

Come up with a goal here or even a few goals for your fight with the IRS because that will help guide your course and help you win.

Step 2: Get Your Transcripts

Next, you want to figure out what you’re fighting over — namely, the tax liability the IRS believes that you owe.

There are a few ways to do this, but perhaps the most straightforward way is to obtain your transcripts from the IRS for each year you want to fight the IRS over.

You can pull your transcripts at irs.gov/individuals/get-transcript.

Now, for any given year, there are four different kinds of IRS transcripts — the tax return transcript, the tax account transcript, the record of account transcript, and the wage and income transcript — but the only two that I typically pull for my own clients are the tax account transcript and the wage and income transcript.

Your IRS tax account transcript is a record of what the IRS thinks you owe for the year. It shows you your balance with the IRS — these are the taxes that you currently owe plus any assessed taxes and interest — as well as any accrued interest and penalties that have not been assessed yet.

Your IRS wage and income is a record of what the IRS thinks you made during the year. It shows the wage and income information that was reported to the IRS for that tax year on forms such as W-2s, 1099s, K-1s, etc.

Step 3: Check For Errors in Your Transcripts

I’ll admit — IRS transcripts can be difficult to read and understand.

But it’s vitally important that you review them for any errors that could help you in your fight against the IRS.

Sp let’s start with the easier one — the wage and income transcript.

Checking Your Wage and Income Transcript

Your wage and income transcript lists out all the wage and income tax documents that were filed with the IRS under your Social Security number.

Understand that these documents were prepared by third parties — your employer in the cases of W-2s, a company you worked for in a non-employee capacity in the cases of 1099-NECs, etc. — and it’s possible a given third party made a mistake in reporting your income on the form.

So go through each document indicated on your wage and income transcript and make sure that all the information presented makes sense and aligns with your own records.

Checking Your Account Transcript

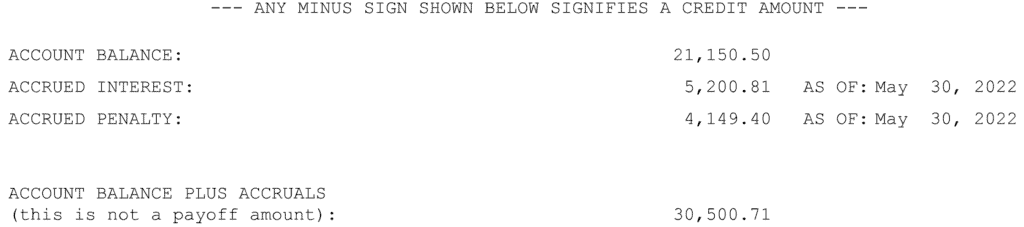

On the first page of your account transcript, you will see the total amount that the IRS believes that you owe it. These amounts are broken down into four line items:

- Account Balance: This is the total taxes, penalties, and interest that the IRS has assessed to your account.

- Accrued Interest: This is the amount of interest that has accrued on your account but has not yet been assessed.

- Accrued Penalty: This is the amount of penalties that have accrued on your account but have not yet been assessed.

- Account Balance Plus Accruals: This amount is the sum of the first three amounts. This is the total amount the IRS believes you owe for the year in question.

Does the total amount look correct? Keep in mind that a significant amount of penalties and interest may have inflated your balance over time.

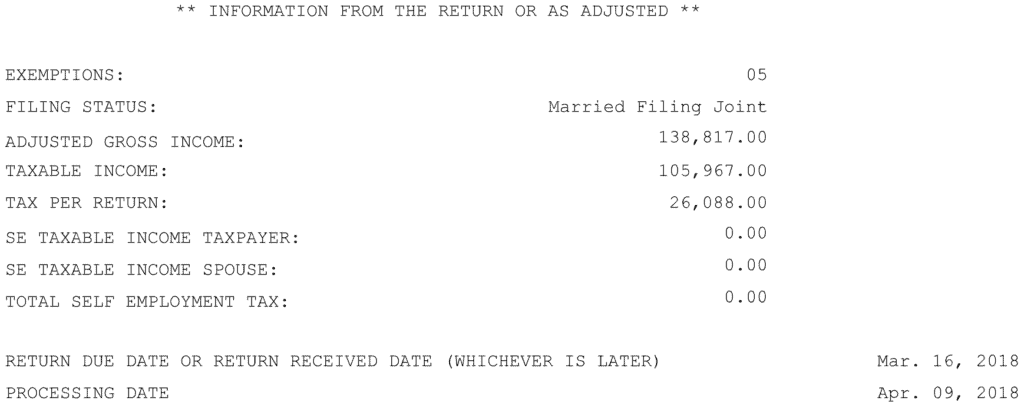

The next section of the account transcript is information from the tax return you filed for the year — or, if you didn’t file a return for the year, information from the substitute for return (SFR) the IRS may have filed for you.

If you have a copy of your tax return, compare the numbers on it to the numbers on this transcript.

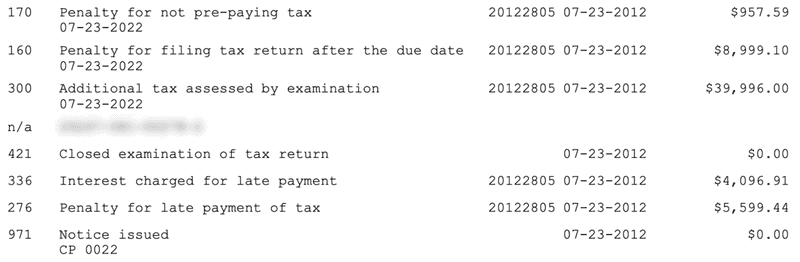

Then the next thing you’ll see on your transcript is all the transactions pertaining to your account for the tax year for the account transcript you’re looking at.

And each of these transactions have different codes on them. I can’t go through all of them because there are just too many, but example codes could be:

- Code 140: Inquiry for non-filing of tax return — This is when the IRS thinks you should have filed a tax return and you didn’t.

- Code 300: The assessment of tax.

- Code 160: The assessment of a failure-to-file penalty.

- Code 276: The assessment of a failure-to-pay penalty.

- Code 336: Interest.

- Code 582: The filing of a lien.

- Code 150: Substitute tax return prepared by IRS — This is when you don’t file your own return and the IRS prepares one for you.

Step 4: If SFRs Have Been Filed, Consider Filing Returns For Those Years

If you see Code 150 on your account transcript, that means that the IRS prepared a substitute for return (SFR) for you for that year.

An SFR is a tax return filing that the IRS will sometimes prepare for taxpayers who do not file a tax return for a given year. An SFR for a given year will generally be based strictly on the wage and income transcript for that year.

![]()

Then, further down on your account transcript, you will see the actual assessment of taxes, penalties, and interest based on this SFR.

If the IRS has prepared a substitute for return (SFR) for you for a given year, consider whether you should file an actual return for that year.

This is generally advisable if filing an actual return will result in a lower tax liability than that reflected on the SFR.

However, if you are a good candidate for an offer in compromise or for currently not collectible (CNC) status and you expect to be able to remain in CNC status until the collection statute expiration date for the tax balance in question, it may actually make no difference to your situation whether you file a return to correct your tax liability for the year or not and in some cases could even make you a better offer in compromise candidate.

Step 5: Make Sure You’ve Filed the Last 6 Years of Returns

The IRS will generally require you to be in tax filing compliance before they will entertain the notion of agreeing to some kind of tax resolution for you — before they will let you “fight” them.

The good news is that the IRS’s policy for what constitutes tax return filing compliance is found in Policy Statement 5-133, which requires tax returns to be filed only for the last six years (to the extent required).

So ensure that you have filed the last six years’ of tax returns to the extent these returns are required.

And waiting for tax returns older than three tax years to be processed is certainly an exercise in patience because these returns will have to be paper filed.

For more information on and strategies for filing past-due tax returns, check out this article.

Step 6: Contest Any Remaining Overstated Liabilities

At this point, you’ve filed returns to correct any SFRs with overstated liabilities — if doing so made sense — and you’ve filed the last six years of tax returns.

So in most cases, once you’ve done those things, and those returns are processed, you and the IRS should pretty much be on the same page in terms of your outstanding tax liability.

However, there are sometimes issues with certain tax years where you and the IRS may still disagree on what you owe for the year.

An example of this is when you and the IRS disagree about certain items on a previously-filed tax return.

There are a myriad of things you and the IRS could disagree about on an already-filed return — contested basis, aggressive deductions, certain tax positions, and more — so I’m not going to go through all the examples here, but I will say if you and the IRS are butting heads on a particular issue where you’re convinced you’re right and the IRS is obviously convinced they’re right, don’t hesitate to reach out to us at Choice Tax Relief.

Step 7: Look Into Penalty Removal

If you owe the IRS, you likely have some penalties that have been assessed over the years.

There are over 150 penalty provisions in the Internal Revenue Code, but the most common penalties are the failure-to-pay penalty, which is the penalty for not paying your taxes on time, and the failure-to-file penalty, which is the penalty for not filing your taxes on time.

If you filed your tax returns on time but simply didn’t pay the tax, you would only be subject to the failure-to-pay penalty.

However, if you filed your tax returns late and you didn’t pay the tax due on them, you would be subject to both the failure-to-pay penalty and the failure-to-file penalty.

We routinely work with clients who have tens — and sometimes hundreds — of thousands of dollars worth of tax penalties on their account.

The good news, however, is that the IRS is known to forgive these penalties from time to time. This process is known as penalty abatement, and it can be well worth your time.

Step 8: Determine Your Tax Relief Options

At this point, you and the IRS should be on the same page in terms of how much you owe them; your liability is no longer in question.

You’ve also done your best to get the IRS to forgive penalties on your account.

If at this point both you and the government agree that you no longer have a liability, great! There’s nothing more to do.

But if you do owe a balance to the government, you have to figure out how to tackle it.

If you are willing and able to pay your balance off with the IRS right now, you can certainly do that; doing so will stop the accrual of additional interest and penalties, if applicable.

However, if you cannot afford to pay off your balance to the IRS right now, you must work out a deal with them that works for both of you.

The most common tax resolution options available to taxpayers are below, and whether you qualify for one of them depends on how much tax debt you have, when it drops off due to the 10-year collection statute of limitations, and your financial situation.

(Note that in this article, I am not going in depth as to how to qualify for each option — this information is covered in depth in the linked-to articles at the end of each section below.)

Installment Agreement

An installment agreement is an agreement with the IRS to pay your taxes over time.

While the IRS generally wants to push taxpayers into a payment of their full tax balance — including penalties and interest — over 72 months, there are often other, more taxpayer-friendly installment agreement options.

In fact, some installment agreements — known as partial-payment installment agreements — can result in the taxpayer actually having some of their tax debt written off.

Learn More: What You Need to Know About IRS Installment Agreements

Currently Not Collectible Status

Currently not collectible status is a status taxpayers can enter into if they can show the IRS that they cannot afford to pay them.

While a taxpayer is in currently not collectible status, the IRS cannot garnish their wages nor levy their bank accounts (though they may still file a notice of federal tax lien).

However, if a taxpayer can stay in currently not collectible status until the statute of limitations — that is, the length of time the IRS has to collect their debt — runs out, the taxpayer’s tax debt will be written off and they will not have had to pay the IRS a dime.

Learn More: What Is IRS Currently Not Collectible Status?

Offer in Compromise

An offer in compromise is an agreement between a taxpayer and the IRS to settle their tax debt for less than they owe.

There are three kinds of offers in compromise:

- Doubt As to Collectibility: a settlement with the IRS on the basis that the taxpayer cannot afford to pay their entire balance and so the IRS would be better off accepting a lower amount

- Doubt As to Liability: a settlement with the IRS on the basis that the taxpayer does not actually owe the amount that the IRS believes they do

- Effective Tax Administration: a settlement with the IRS on the basis that forcing the taxpayer to pay their balance due would be unfair on the basis of hardship, public policy, or equity

Although — for obvious reasons — many taxpayers want to pursue an offer in compromise, not all taxpayers qualify for this kind of tax relief.

Learn More: How Much to Offer in Compromise to the IRS

Step 9: Pursue the Resolution

Once you’ve decided which tax resolution option for which you qualify is best for you, you must then pursue it.

For currently not collectible status and some installment agreements, this can be as easy as picking up the phone with the IRS, explaining your financial situation, and submitting to them any documentation they request.

For more aggressive installment agreements as well as an offer in compromise, you will generally have to submit special forms to the IRS to establish your position.

For an installment agreement, these forms may be, for example, Form 9465 and Form 433-A; for a doubt as to collectibility offer in compromise, on the other hand, the forms in question are Form 656 and Form 433-A (OIC).

Note that after you submit your currently not collectible status or installment agreement request, you may have to wait a few weeks for the IRS to approve it.

But that’s really not all that bad compared to the 7-to-12-month waiting time for the IRS to respond to an offer in compromise!

Step 10: Remain in Compliance

After you establish a resolution for your existing tax debt, it’s important that you stay in compliance by filing all required returns, making all required estimated tax payments, and making sure you’ve paid in your full balance for the tax year before its due date (generally April 15 of the following year).

If you don’t remain in compliance with your current tax obligations, the results could be disastrous.

Failing to pay in your current taxes, for example, could cause you to default on your installment agreement or offer in compromise, and you’d have to start your fight with the IRS all over again!