How to File Your Back Taxes, Avoid Penalties, and Get Your Life Back on Track

Every day, my team and I speak with people who have not filed their tax returns.

Whether you’re being hounded by the IRS, want to claim a refund that you’re owed, or just want to file your returns now, the information I discuss here pertains to you.

Here’s what you’ll learn in this article:

- The consequences of not filing your taxes

- How the IRS treats individuals who don’t file tax returns

- Practical tips on how to file your back taxes

Table of Contents

Why Don’t People File Tax Returns?

There are lots of reasons why people don’t file their taxes, and as a CPA, I’ve seen them all.

Often, people get behind on their taxes because they simply don’t think they have to file.

This frequently occurs with younger adults who still live at home and just work a part-time job and with older adults who recently retired.

Other people put off filing their taxes because they know they’re owed a refund and think the IRS won’t care if they don’t file, or because they owe a large sum and think not filing will help the situation.

Perhaps most commonly, people don’t file their tax returns because life happens; a traumatic experience occurs, causing them to fail to file one return, it all goes downhill from there, and next thing they know a decade has gone by and they haven’t filed a single tax return.

In my experience, failure to file a tax return frequently snowballs — the next tax season rolls around and many people feel so overwhelmed by the need to file two returns that they don’t file at all.

As a result, the IRS sends several notices, the CP59, CP515, CP516, and CP518, all of which warn the recipient to pay the late taxes in increasingly strong language. Often, though, people don’t even open the warning letters they receive from the IRS because they feel too overwhelmed and are scared to face the consequences of late taxes.

In reality, you don’t need to be scared; hundreds of thousands of Americans receive these notices each year without going to jail. While interest and penalties accrue, the interest has been relatively low over the past decade and you can sometimes get the penalties abated. However, the solution starts when you deal with the issue and muster up that little bit of courage to file your tax returns, not when you let it get worse and worse.

That being said, if you want someone to handle this for you, you can schedule a free consultation with me or one of my tax managers by calling 866-8000-TAX. Our prices aren’t cheap, but they aren’t the most expensive either, and we have people who specialize in helping you pay your back taxes.

Consequences of Not Filing Tax Returns

In addition to the nagging feeling of knowing that you’re behind on your taxes, there are some very real consequences of not filing your tax returns.

Penalties

The IRS has many various penalties it imposes, which I’ll address in more detail in an upcoming Youtube video, but in terms of back taxes, the two main penalties are failure to file and failure to pay.

Failure-to-File Penalty

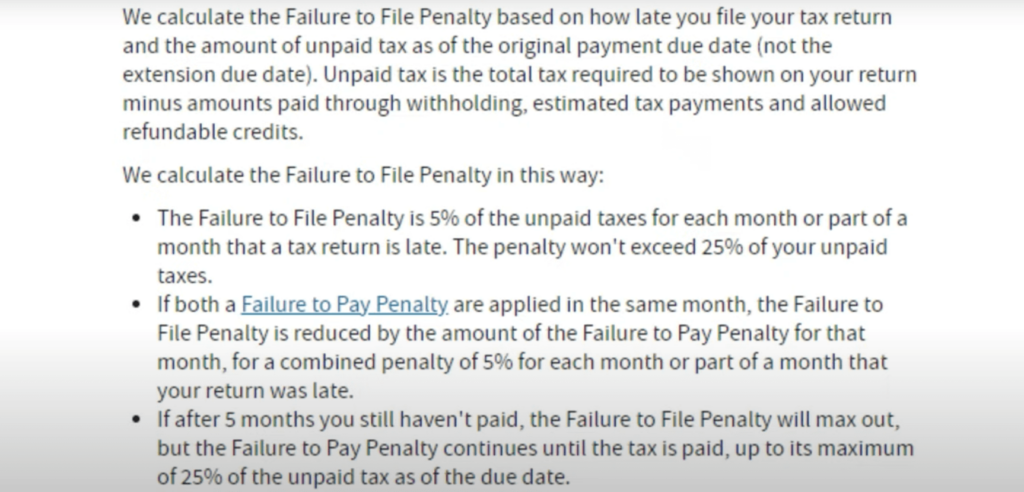

The failure-to-file penalty, equal to five percent of your unpaid taxes for each month or part of a month your return is late, takes effect when you don’t file your tax return by either the original due date or the extended due date (if you filed for an extension) and maxes out at 25% of your unpaid taxes.

If your tax return is over 60 days late, the minimum failure-to-file penalty is either $435 or 100% of the tax required to be shown on your return, depending on which is the lesser.

Failure-to-Pay Penalty

The failure-to-pay penalty, which also maxes out at 25%, is equal to .5% of your unpaid taxes for each month or part of a month past the due date that the tax remains unpaid.

If you owe both penalties, the failure-to-pay penalty will be subtracted from the failure-to-file penalty each month. In other words, your maximum combined failure-to-file and failure-to-pay penalty is equal to five percent of your unpaid taxes each month.

Combined, these penalties max out at 47.5% four years and two months after the due date. Thus, if you haven’t filed a tax return that was due four or more years ago, you could be looking at a substantial almost-50% penalty on your tax due.

Interest

The IRS charges interest, which compounds daily on your balance, on both your tax due and your penalty. The interest rate equals the federal short-term rate plus three percent. Currently, this means the interest rate is equal to three percent because the federal short-term rate is extremely low, but this could change when the federal short-term rate is adjusted (which happens every three months).

Loss of Refund

Even if you don’t owe taxes, late tax returns come with penalties. In fact, according to the refund statute of limitations, you must file your tax return within three years of the due date to receive a refund for the IRS for a given tax year. After this time expires, the IRS will neither send you a refund for the tax year nor apply any credits for that tax year to other tax years that are underpaid.

Inability to Get Loans

In order to get various types of loans or mortgages, you’re often required to present your tax return(s), so if you don’t have them, you may not be able to take out most loans. You also can’t get student aid without your tax returns.

Ineligibility for Stimulus Payments

As we saw during the pandemic, Congress occasionally passes some stimulus bills and other payments. If you haven’t filed your tax returns, you may not receive this money since the distribution is generally based on tax returns.

Immigration Issues

If you’re a permanent resident with a green card but fail to file a tax return, you may be considered to have abandoned your permanent resident status and may lose it.

Loss of Some Social Security Income

If you’re self-employed, you won’t accumulate any Social Security credits for your self-employment income if your earnings aren’t reported within three years, three months, and 15 days of the end of the year in which you earned the income, so you may lose future Social Security benefits if you don’t file your tax returns.

Substitute for Returns (SFRs)

If you don’t file your tax return, the IRS might prepare a return for you and calculate the tax due on its own. If it gets to this point, the IRS will assess tax and possibly start collection activities (liens, levies, etc.) on its own regardless of whether you owe what the IRS thinks you owe.

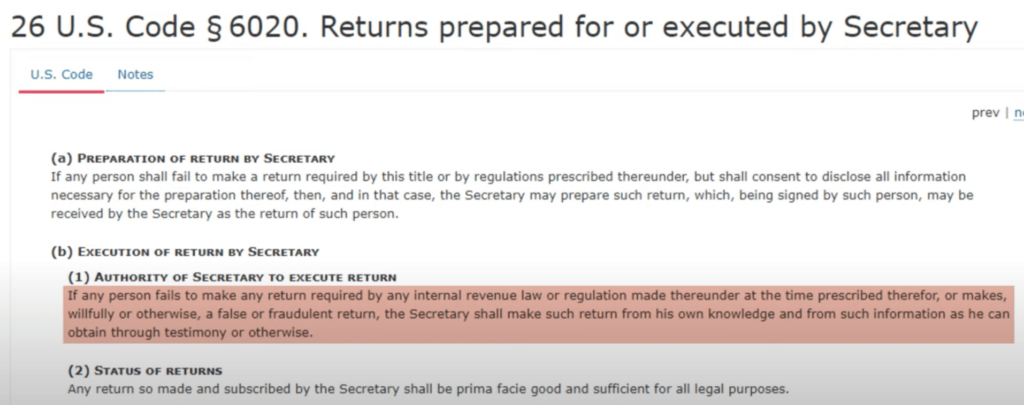

Under Section 6020(b) of the Internal Revenue Code, the IRS has the authority to prepare its own tax return and process that return when a taxpayer fails to file a required return or files a false or fraudulent return. This IRS-prepared return is called a substitute for return (SFR), and not only can the IRS prepare and process this return, but it can also assess the tax accordingly.

SFRs and the Statute of Limitations

While the ten-year statute of limitations for collections starts when the IRS assesses the tax based on the SFR, the statute for assessment — the amount of time the IRS has to go back to a tax year and assess tax — doesn’t apply when the IRS prepares an SFR for you.

Normally, the IRS only has three years from the due date of the return or the filing date of the return to assess tax or additional tax, but this means that the IRS can indefinitely assess tax or additional tax on a year you never filed a tax return for.

I’m planning to release a video with more detail on IRS statutes of limitation in the future, but for now, that’s beyond the scope of this discussion.

Reasons Why SFRs Are Usually Bad

Not everyone who fails to file a tax return has an SFR prepared for them. For example, if you just have a W-2 and aren’t significantly underwithheld or are overwithheld, the IRS probably won’t file an SFR for you for that year.

If the IRS does prepare a SFR for you, though, that SFR is sufficient for all legal purposes. However, this may not be good for you for several reasons.

Wrong Filing Status and Number of Dependents

First, the IRS may use the wrong filing status for you. On SFRs, the IRS only uses single filing status and married filing separately status. In reality, though, if you’re unmarried, head of household might be better for you (if you qualify), and if you’re married, married filing jointly might be better for you.

Further, the IRS may not even know about some of your dependents, so it may not take them into account when creating your return.

No Itemized Deductions

On an SFR, the IRS also only gives you the standard deduction and does not itemize your deductions. Thus, even if you have itemized deductions in excess of your standard deduction, the IRS will just use the standard deduction for your filing status on the SFR it prepares for you.

No Business Expenses

If you’re self-employed, the IRS will calculate your self-employment income with your gross receipts reported on a 1099; it doesn’t know your business expenses, so it won’t deduct those for you.

Possibly Incorrect Stock Basis

Finally, the IRS doesn’t know your basis for all your securities, so when it receives your 1099-B with your proceeds, it just gives you zero basis on your SFR.

Filing a tax return is essential in terms of telling the IRS what your basis, business expenses, and itemized deductions are. Most of the time, then, the IRS-prepared Substitute for Return will not work in your favor and will probably indicate that you owe more than you would if you actually filed your tax return.

How to File Back Taxes

Like I already said, you could reach out to a professional to file your missing tax returns for you. If you’re interested in this, you can call 866-8000-TAX to schedule a free consultation with one of our tax professionals.

However, in this section, I’m going to provide you with some practical tips for filing back taxes yourself.

Step 1: Determine which tax years to file for.

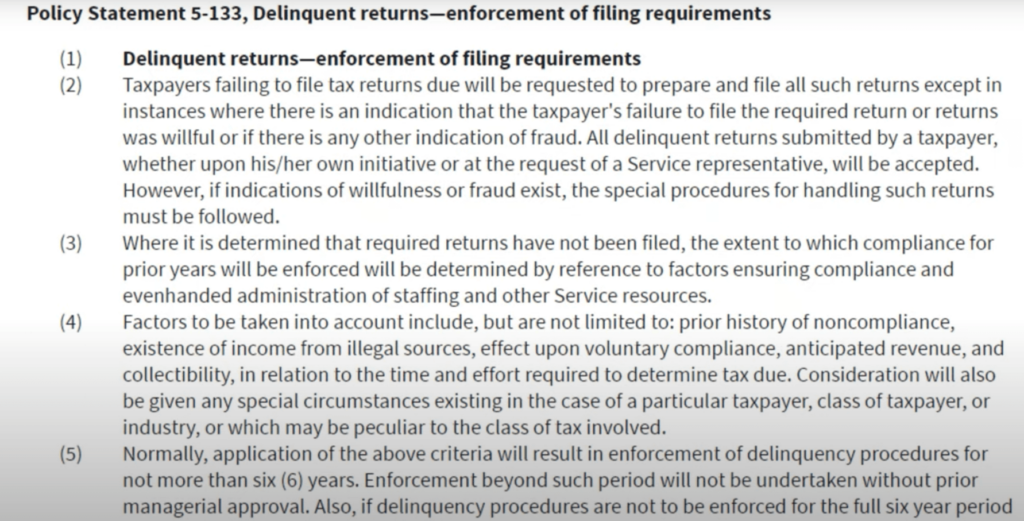

It’s important to note that you may not have to file all your missing tax returns. According to the IRS’s 2006 Policy Statement 5-133, it’s generally sufficient to file the past six years’ worth of tax returns to be considered in compliance. For the IRS to go farther back, it needs managerial approval.

Thus, if you haven’t filed tax returns from more than six years ago but haven’t received any letters from the IRS concerning them, it might be best to let sleeping dogs lie. If you do, though, bear in mind that the statute of limitations on assessment doesn’t apply.

However, if the IRS is hounding you to file an old return or has prepared, processed, and/or assessed an SFR that overstates your tax liability, you may want to file for that year.

Step 2: Determine which tax year to file first.

After you’ve figured out which years you should file for, you should consider which years you should file tax returns for first considering the refund statute of limitations. For example, if you’re filing your returns in late March or early April 2022, your ability to collect a refund will soon expire for taxes due in 2019 without regard to extension, meaning your 2018 tax return.

In this case, then, you might want to work through your 2018 return first to see if you’re owed a refund for that year. If you are, you should prioritize completing that 2018 return before the expiration of the refund statute on April 15, 2022. Bear in mind that this date may differ if the April 15 for the year of the due date fell on a holiday.

If you’re approaching a current-year tax filing deadline, you may want to prioritize the current year.

Excluding these two situations, it’s usually a good idea to go in order by starting with the oldest missing tax return since tax items can carry forward from year to year.

For example, if you sold some stocks for a $10,000 loss in 2017 and had no other gains or losses that year, you would only be able to deduct $3,000 on your 2017 tax return. The remaining $7,000 would be carried forward to future years, so if you did the later returns first, you might not take into account the capital loss carryforward.

Thus, considering the many different types of carryforwards, I generally prefer to file tax returns sequentially.

Step 3: Get your IRS transcript.

The next step is to get your IRS transcript- which you can do online at irs.gov/individuals/get-transcript– for each year you need to file a tax return for.

Why? On your transcript, you can see all the 1099s, W-2s, K-1s, 1099-Bs, etc., that the IRS has received for you for a given year, so you can check to make sure you have the information that you need to file your returns.

When you pull your transcripts, you can also see if the IRS has prepared an SFR for you. If it has and the amount due is less than you actually owe, you may be faced with an ethical dilemma regarding whether you should file or not. I’m not going to speak to this here, but if you’re in this position, you can schedule a free consultation at 866-8000-TAX.

Step 4: Reconstruct your data and prepare your returns.

By checking your transcripts, you can confirm that you have all the information reported on third-party-prepared tax forms like 1099s and W-2s. However, some items of income and expense aren’t reported on a 1099 or W2; if you’re self-employed, the IRS doesn’t know how much you received or your expenses. At the same time, though, you probably don’t know your income and expenses for X tax year three or four years ago.

If this is the case, you have to “reconstruct” your income and expenses for the year using credible evidence. Usually, this includes pulling your bank statements and then looking at other third-party information. Things like property taxes and DMV fees you can look up online, while you can find your medical expenses by requesting records from the provider or insurance company. You can also determine the state withholdings by checking the state department of revenue or requesting them from your employer.

You also need to pull brokerage statements to make sure the IRS hasn’t left out your basis. Occasionally, your brokerage may not have the records, so you might have to go back and look at the closing stock price by date.

Clearly, there’s a lot to consider when reconstructing records, especially if you have your own business. However, if you’re a business owner, there are several additional resources you can use to help you throughout this process.

First, the IRS has a list of guides for various industries, called the IRS Audit Technique Guides, which are designed to help its own auditors audit specific businesses.

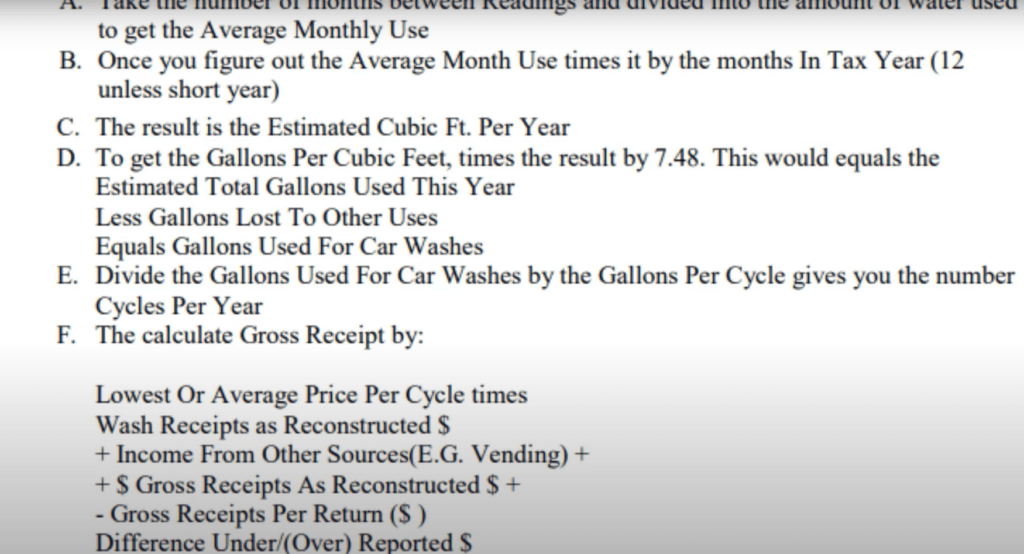

For example, this shows part of the guide for car washes, which has information on what the IRS wants its auditors to consider when attempting to calculate gross receipts, including formulas for calculating various expenses.

Thus, if you own a car wash (or other business) and don’t know your receipts for the year you didn’t file for, you can use the IRS formula and, if questioned by the IRS, explain that you followed their own guidelines.

You can also use bizminer.com and bizstats.com as aids when reconstructing your expenses. Both these sites give industry averages for various expenses and can be used to estimate your expenses. In fact, in the Tax Court Memorandum Decision David W. Bauer vs. the Commissioner of Internal Revenue, the Tax Court held that the taxpayer in question could “deduct an estimated amount of contract labor expenses for each tax year at issue using the 2006 average ratio found in the BizMiner report.”

Thus, if you’re a business owner and have no idea where to start, it might be a good idea to check out some of these resources.

When preparing your old returns, bear in mind that the tax laws in place for a given year still apply. Even though you’re preparing the return now, you can’t apply the current tax laws. Your tax software will handle this for you, but it’s important to remember as you’re planning.

Step 5: File your returns.

You can e-file your tax returns for the current year as well as the two preceding tax years. This is easy and can be done through your tax software.

To file older taxes, though, you’ll have to mail in your returns. In my opinion, you should use either USPS return receipt requested or a private delivery service rather than regular mail to mail these returns.

I also recommend either sending your paper-filed returns in separate envelopes or putting each in its own envelope and then putting them all in one main envelope. Why? If you mail them all in the same envelope, there’s a chance that the IRS may just look at the first page and indicate that only one of your returns was received even though you sent all of them. This happened to one of my clients in the past, and while I was able to resolve it, it’s ultimately better to prevent it from happening in the first place by sending them separately or in separate envelopes.

Penalty Abatement

There are two main types of penalty abatement for back taxes: first-time abatement and abatement for reasonable cause. There’s another penalty abatement called statutory exception, but that’s relatively rare since you have to prove that the IRS provided you with erroneous advice.

First-Time Abatement (FTA)

First-time abatement can be used to abate failure-to-file, failure-to-pay, and failure-to-deposit penalties based on the premise that everyone deserves a second chance. This usually applies only to your first year of back taxes and requires you to be in compliance, so it’s generally something to attempt after you’ve filed your returns. Again, you can only get this on one tax year, usually the oldest you didn’t file for.

Relief for Reasonable Cause

Relief for reasonable cause depends on providing the IRS some sort of reason you weren’t able to file and pay your taxes on time. When doing this, you need to pull all the strings. For example, if you’re 65 or older, you should refer to yourself as elderly since it can be more effective to say that the “elderly” taxpayer was unable to file X tax returns for whatever reason.

I normally wouldn’t refer to a 65-year-old as elderly and I understand that this may sound offensive to some. However, when filing for relief for reasonable cause, it’s important to use turns of phrase like that since there are real people at the IRS making determinations based on their judgment.